advocacy

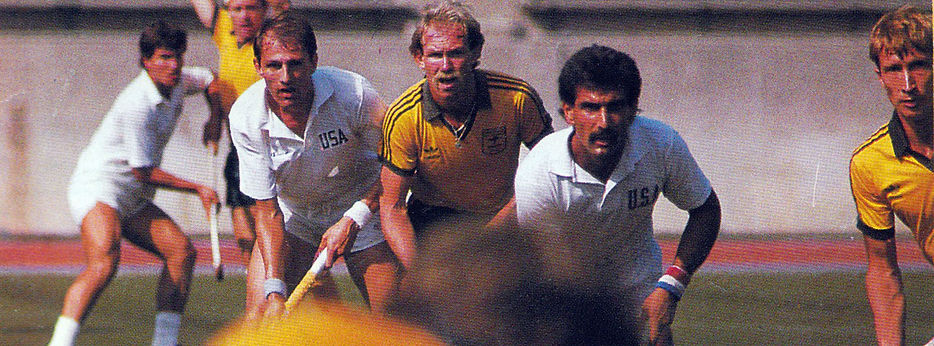

The Olympic Games have represented athletic excellence, cultural exchange, and, at times, political messages and opinions. Many today are exposed to the stories of athletes who represent highly publicised mainstream sports, however, there are many stories of athletes who have dedicated their lives to their sport and to representing their country at the Olympic Games that go unnoticed. One of these stories being that of Manzar Iqbal, whose story I hope to bring to light, a U.S. Olympic field hockey player who competed at the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, California. His journey is a testament to perseverance, passion, and cultural identity.

Born in Lahore, Pakistan, Manzar Iqbal’s connection to field hockey was, in many ways, predestined. His father had played the sport in pre-partition India before relocating to California, where Manzar grew up playing soccer and tennis. After around eight years in the U.S., his father found a community of field hockey players and offered Manzar an enticing ultimatum regarding his weekend activities— yard work or field hockey with his father. Unsurprisingly, he chose the game and began his journey as a player. Though he started playing much later than others, Manzar’s positioning skills from soccer and hand-eye coordination from tennis made him a perfect fit for field hockey. A combination of genetic strengths from his German mother and Pakistani father enabled him to quickly adapt and excel in the sport.

To Manzar, one of the most appealing aspects of field hockey was its international nature. When he began playing, the sport was diverse, with players from many different cultural backgrounds coming together, similar to his multicultural environment at home. His journey took him to the University of California, Berkeley, where he was originally playing soccer. However, after falling ill his doctor recommended against playing a contact sport. Ironically, he turned to field hockey, an even more physical game. Throughout his time at Berkeley, Manzar got to train with his teammates and also the U.S. women’s team who were preparing for the 1980 Olympics in Moscow— an event ultimately boycotted by the U.S. government and over 60 other nations in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan which was intended to support a communist regime. Despite the missed opportunity for those athletes, the camaraderie within the sport left a lasting impact on Manzar.

With two years until the 1984 Olympics, Manzar, a fresh graduate from UCB, moved to Southern California alongside all the U.S. field hockey players to train together. While many ask him about his memories of the Games, Manzar often reflects not on the two weeks of the competition but the six years of intense preparation leading up to them. His path that led him to the Olympics was shaped by diligence and an unwavering commitment to his sport.

Looking back at his career, Manzar reflects on moments when he could’ve spoken out about issues that didn’t align with his values. At the time, he acknowledges he was younger and may have been hesitant to risk friction with his teammates. However, with experience, he now understands how he would approach those moments with greater confidence today.

The Olympics, in his experience, fostered mutual respect among athletes, regardless of their sport. However, he believed that field hockey, lacking the spotlight of sports like soccer and tennis, did not provide the same platform for advocacy. Today, he recognized that he could’ve taken a stand on various issues within his team and the broader sports community. Some athletes have more of a platform to voice their beliefs whereas others choose to remain focused solely on their sports and not mix it with political beliefs. Despite this, Manzar emphasizes the importance of standing firm in one’s values and encourages younger generations to not be afraid of speaking up.

For aspiring athletes, Manzar advice is to trust yourself, respect your own values and the values of those around you, honor your heritage and to speak up for what you believe in. He emphasizes that most teammates will support one another and his own journey has taught him that unity within a team is crucial, but so is individuality.

Through hard work and perseverance, Manzar secured a spot on the U.S. men’s national field hockey team. Alongside the many expatriates on the team, he never felt as though his race or background were viewed as limiting. Wanting to improve his skills, Manzar took time off school and spent nine months in Germany training with a club team. Upon returning home, he was eager to share his new expertise in the sport. Manzar often spent time training alone, perfecting his game by practicing against a wall— his ever reliable training partner, rain or shine.

Manzar’s career in field hockey has led him to represent the U.S. over 100 times and compete in four Pan American Games. He continues to play at the Masters level, reinforcing his passion for the sport. He seeks to pass a message to young athletes: representing one’s country is an immense honor and true patriotism embraces diversity. He wants people to see that being American is not defined by a single look or background. While Manzar may not have had the same media presence as athletes in higher-profile sports, his story is no less significant. His journey serves as a reminder that every athlete, regardless of their sport can be a messenger for their culture, beliefs and values they hold. His Olympic experience may have passed by in a flash, but the lessons and experiences he gained from them continue to shape his perspective and inspire others to this day.